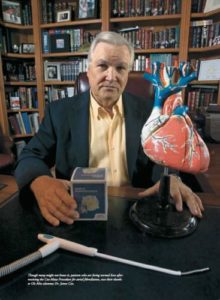

Dr. James Cox – Alumnus Spotlight

Dr. James L Cox (BS chemistry ’64) is a retired cardiothoracic surgeon – the Evarts A. Graham Professor of Surgery Emeritus and Chief of the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery Emeritus – from Washington University School of Medicine, Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis.

Dr. James L Cox (BS chemistry ’64) is a retired cardiothoracic surgeon – the Evarts A. Graham Professor of Surgery Emeritus and Chief of the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery Emeritus – from Washington University School of Medicine, Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis.

Born and raised in Fair Oaks, Arkansas, Dr. Cox was recruited to UM by Johnny Vaught and from 1960 to ’64 played baseball and freshman basketball, was president of Alpha Epsilon Delta, and a member of the Phi Delta Theta Fraternity. After turning down baseball contracts from the San Francisco Giants and Los Angeles Dodgers, he enrolled at University of Tennessee Medical School in 1963. He received his medical degree in 1967 and was awarded outstanding student in his graduating class.

Dr. Cox trained in cardiothoracic surgery at Duke University. He spent the majority of his career as the first Evarts A. Graham Professor of Surgery and chief of the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery at Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes Hospital in St. Louis. He is best known for his work in the field of cardiac arrhythmia surgery and the development of the eponymous “Cox-Maze Procedure” for the treatment of atrial fibrillation. He lives in Atlanta and serves as a senior consultant to eight medical device companies and on the board of directors of four of them.

In 2020 Dr. Cox received the Jackobson Innovation Award of the American College of Surgeons, and international award recognizing life-long pioneering and innovative work in cardiothoracic surgery.

Read an extended profile of Dr. James Cox from the Ole Miss Alumni Review by Tina H. Hahn

Life magazine first offered James L. Cox (BS chemistry ’64) a glimpse of open-heart surgery. The photo of an operation being performed by Dr. Michael E. DeBakey so affected Cox—then a young teen sitting in a dentist’s waiting room—that he decided to pursue a career in cardiovascular surgery.

What’s significant is not only that Cox became a cardiovascular surgeon but that the impact of his work is recognized around the world.

Today Dr. Cox is the Evarts A. Graham Professor of Surgery Emeritus and Chief of the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery Emeritus at Washington University School of Medicine, Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis. His seminal work in the surgical treatment of cardiac arrhythmia ultimately led to the development of the universally known Cox–Maze Procedure. Studies show the 15–year cure rate of 96% for the treatment of atrial fibrillation.

“Dr. Cox will go down as one of the great cardiac surgeons of the 20th century,” said Dr. Ralph J. Damiano Jr., chief of cardiac surgery and Evarts A. Graham Professor of Surgery at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “He developed the first successful surgical procedure for atrial fibrillation 20+ years ago and it remains even today the gold standard.”

Damiano describes the achievement as one of the premier examples of taking a basic hypothesis, testing it in the laboratory, and then applying it to cure disease. “Dr. Cox is considered the father of arrhythmia surgery,” Damiano said. “The operation has cured thousands around the world and restored a normal quality of life. On top of this monumental contribution, Dr. Cox created one of the premier academic units in the world at Washington University, Barnes–Jewish Hospital. Under his leadership, the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery was considered one of the world’s best, both for faculty research and training residents.”

Cox is dedicated to clinical excellence, the development of new techniques, and the training of the next generation of surgeons. To him, the most meaningful accomplishment is that the majority of patients who receive the Cox–Maze procedure lead normal lives. “A few years ago we hosted a reunion of patients who had the procedure. The testimonials patients gave on how the surgery changed their lives were very moving,” Cox said. “If you are lucky enough to live long enough to hear personal stories from patients you’ve helped, well that’s what matters.”

BUILDING A CAREER

To establish his career, Cox began with classes at UM. “The chemistry and biology departments were superb, with excellent teachers,” he said. “I received a great education and was very well prepared for medical school. In fact, I found medical school easier than pre-med school at Ole Miss.” Cox was named most outstanding student in his graduating class at the University of Tennessee Medical School.

His specialization began with a severe knee injury while playing baseball for UM in 1962. A few months later a blood clot developed in his lower leg that traveled to his lungs. Hospitalized for two months, Cox spent his time in bed reading about the heart.

“I read all night,” he recalls 52 years later. “It was like reading a novel.”

“After seeing the photo of Dr. DeBakey in Life magazine during high school, I was always interested in surgery. And I had good eye, hand coordination,” said Cox, who received baseball and basketball scholarships to UM. “In those days the most exciting careers were astronaut, baseball player, or heart surgeon.”

The Los Angeles Dodgers extended an offer to play professional baseball the same day his letter of acceptance to medical school arrived. With multiple injuries playing baseball in college, the choice wasn’t difficult.

“On the first day of medical school, I knew I wanted to be a heart surgeon,” Cox said. “It’s a huge advantage to know your area of interest early on and I was absolutely certain.

“I just wanted to get my degree and stay in Memphis.”

Instead, the next 11 years—except for a two–year stint of active duty in the U.S. Army—were spent in surgical training under the legendary Dr. David C. Sabiston Jr. at Duke University. “It was the best decision I ever made,” Cox said. “It was the hardest training program.”

After training, Cox joined the Duke faculty. In 1983, he was appointed professor and chief of cardiothoracic surgery at Washington University School of Medicine and later named vice chair of the Department of Surgery. Under his leadership, the cardiothoracic division employed 17 cardiothoracic surgeons and 30 researchers supported by eight National Institutes of Health grants.

Dr. Leo Antonovich Bockeria (left), professor and chair of cardiac surgery at the Bakoulev Institute of Cardiac Surgery in Moscow, and Dr. Cox in May 2014.

Cox’s career has focused on understanding the electric signals that prompt the heart to beat out of control and creating techniques to cure the arrhythmia. He developed the Cox–Maze procedure with other physicians and researchers over two decades. “Engineers at Washington University built a computerized mapping system and we mapped patients with atrial fibrillation who were having surgery for other problems,” Cox said. “I realized we could place incisions upon the heart that would interrupt the circuits responsible for the arrhythmia and still leave the atria contracting post–op.”

In 1997, Cox joined Georgetown University as professor and chair of the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery and director of the Georgetown Cardiovascular Institute. A few years later, bilateral knee replacements forced him to give up the clinical practice of surgery. In 2003 Cox rejoined Washington University as Emeritus Evarts A. Graham Professor of Surgery. He developed a new heart valve and a way of implanting it without sutures, while working on a Cox–Maze type method for outpatient procedures and a new 3-D imaging system for the heart.

“My career had a lot of pixie dust and turned out well,” Cox said. “I was well-prepared and worked hard.

“Hard work makes a mediocre person, good and a good person great. It’s like athletics, the hardest worker on the team wins. You learn a lot about life from sports.

“My advice to young people is to be sure you have the commitment to work hard. I ran the largest training program in the country at Washington University for years. In medical school, everyone is equally smart, what separates students is having common sense and being willing to work hard.”

Fast forward 50 years after those Life magazine photos inspired Cox. He has just returned from a trip to the prestigious Russian Academy of Medical Sciences where he is one of two Americans elected as honorary members. The first and only other was Dr. DeBakey, “the legendary Houston doctor who originally got me interested in heart surgery,” Cox said.

In 2000, the University of Paris celebrated the first 50 years of heart surgery and its 29 innovative pioneers with a dinner in the Eiffel Tower. Dr. Cox dined with Dr. DeBakey, the inspiration for his career.

“Jim Cox is one of the guys I love to be around,” said friend Don Kessinger, a former professional baseball player and UM coach. “He is a fun person, a good athlete, and a great student. I am so proud of what Jim has accomplished in his career. It’s been thrilling to watch it unfold.”